-40%

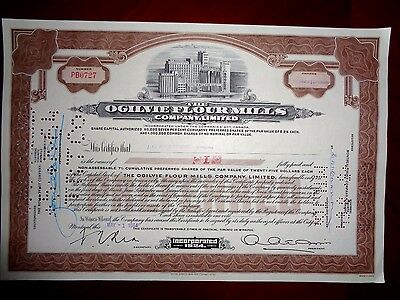

CANADA OGILVIE FLOUR MILLS stock certificate 1964

$ 14.25

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

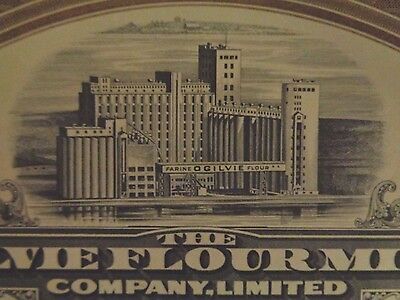

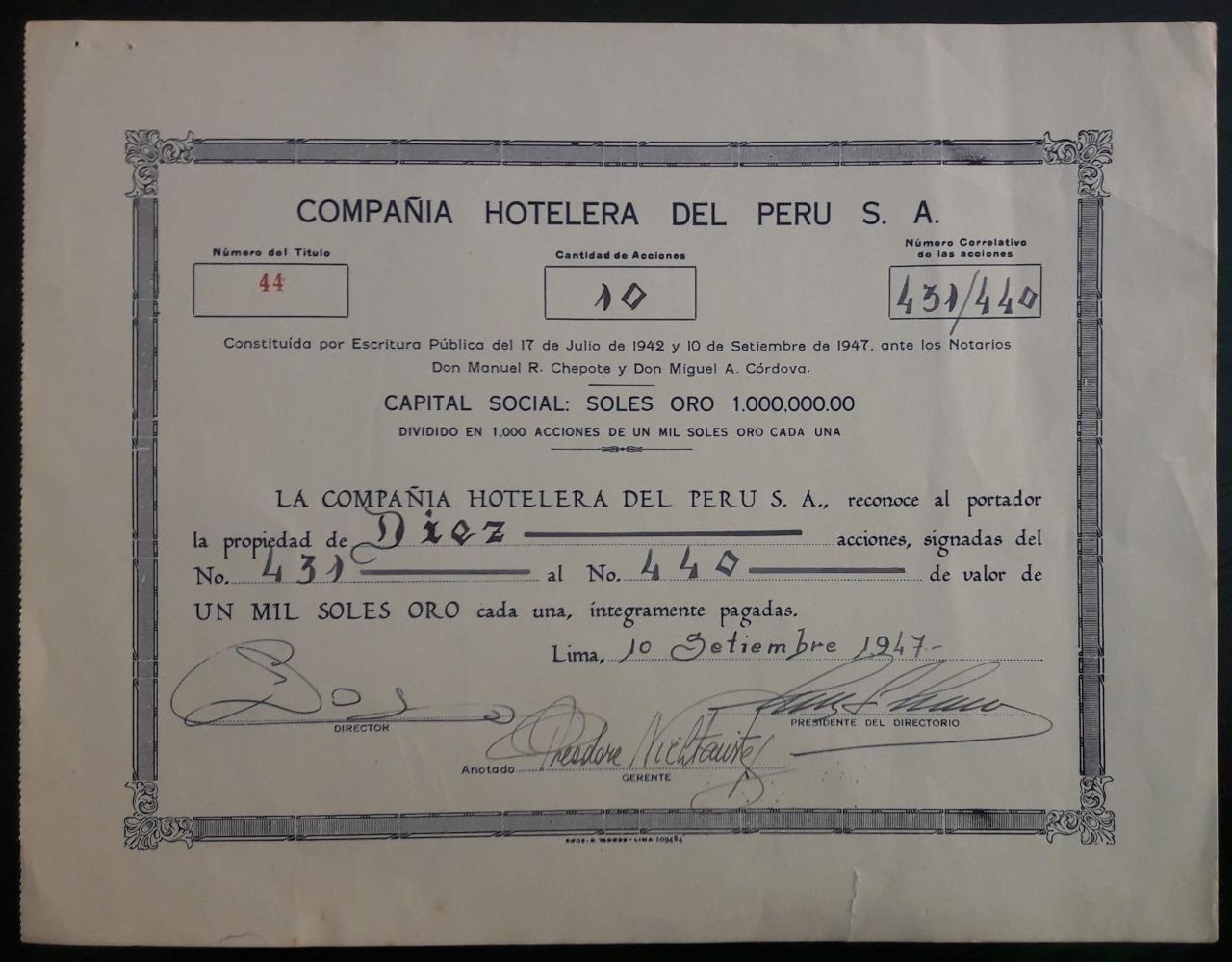

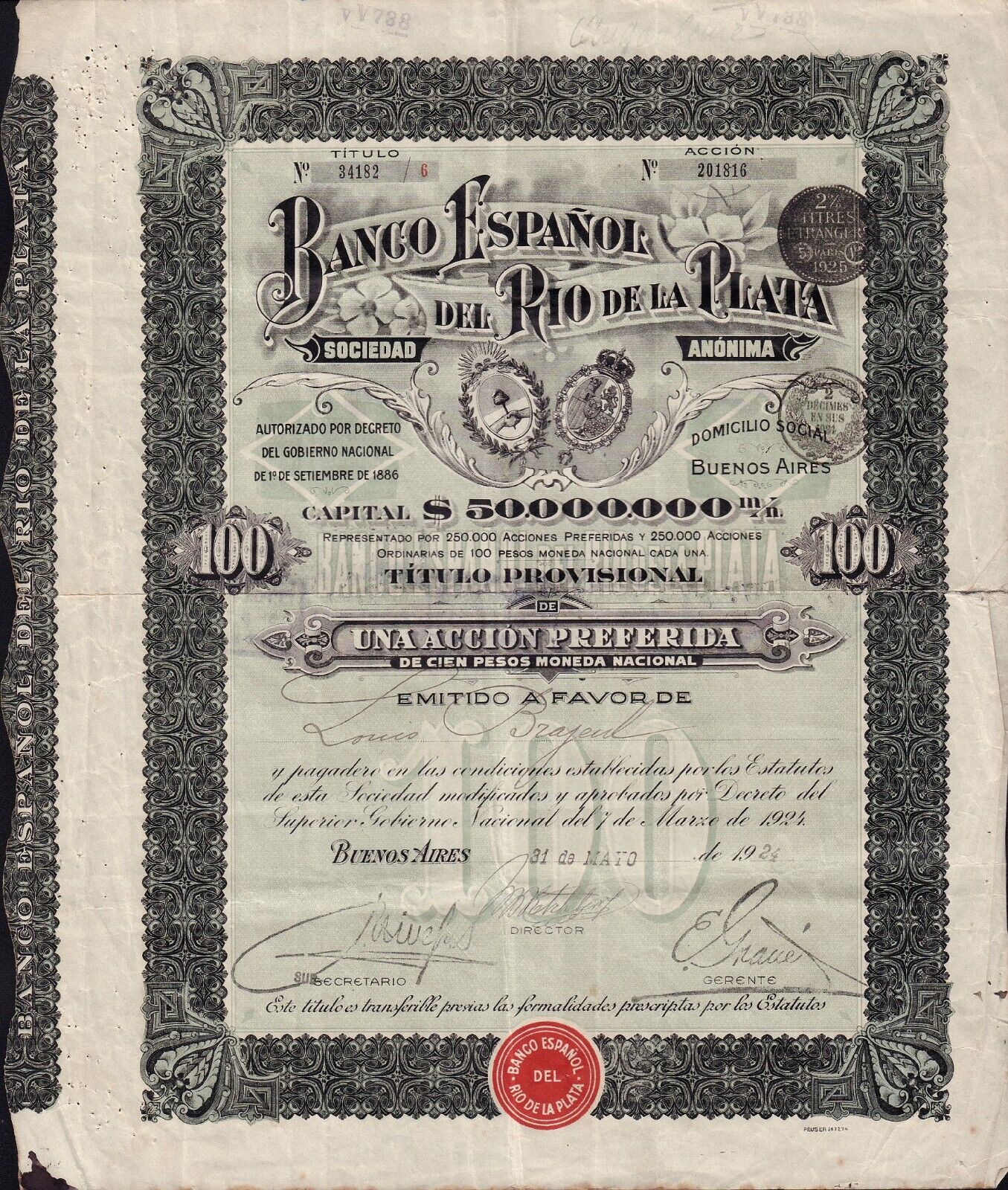

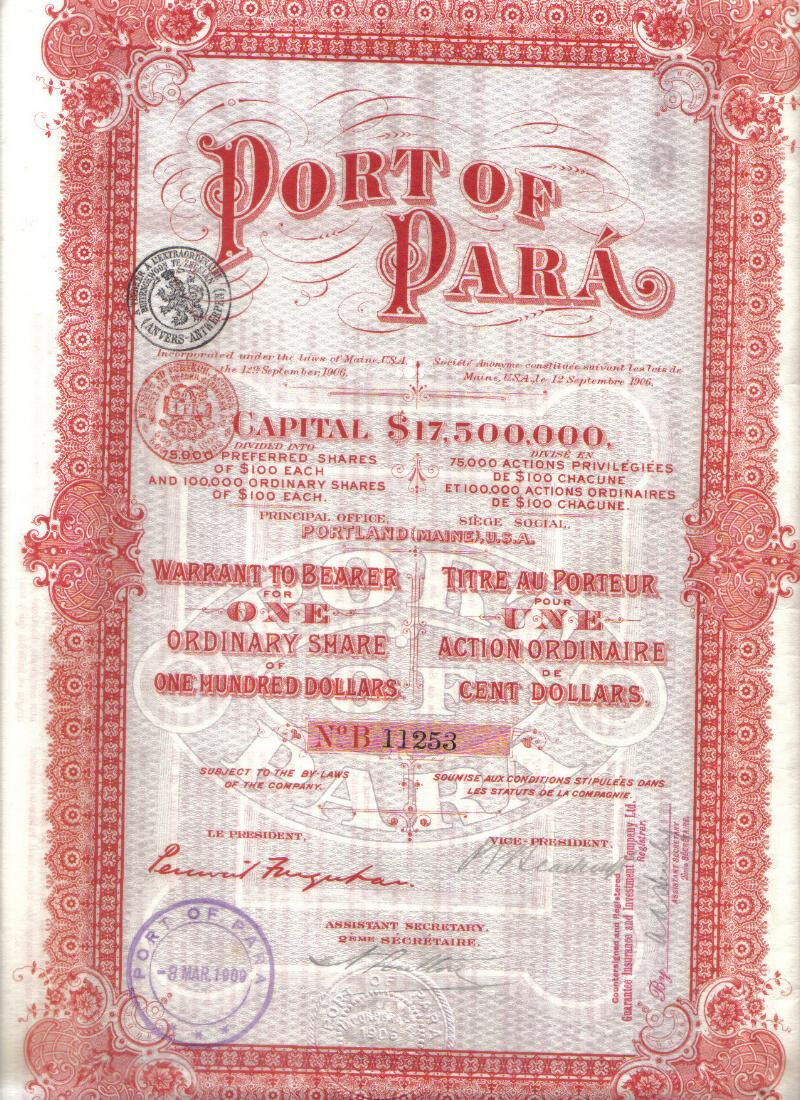

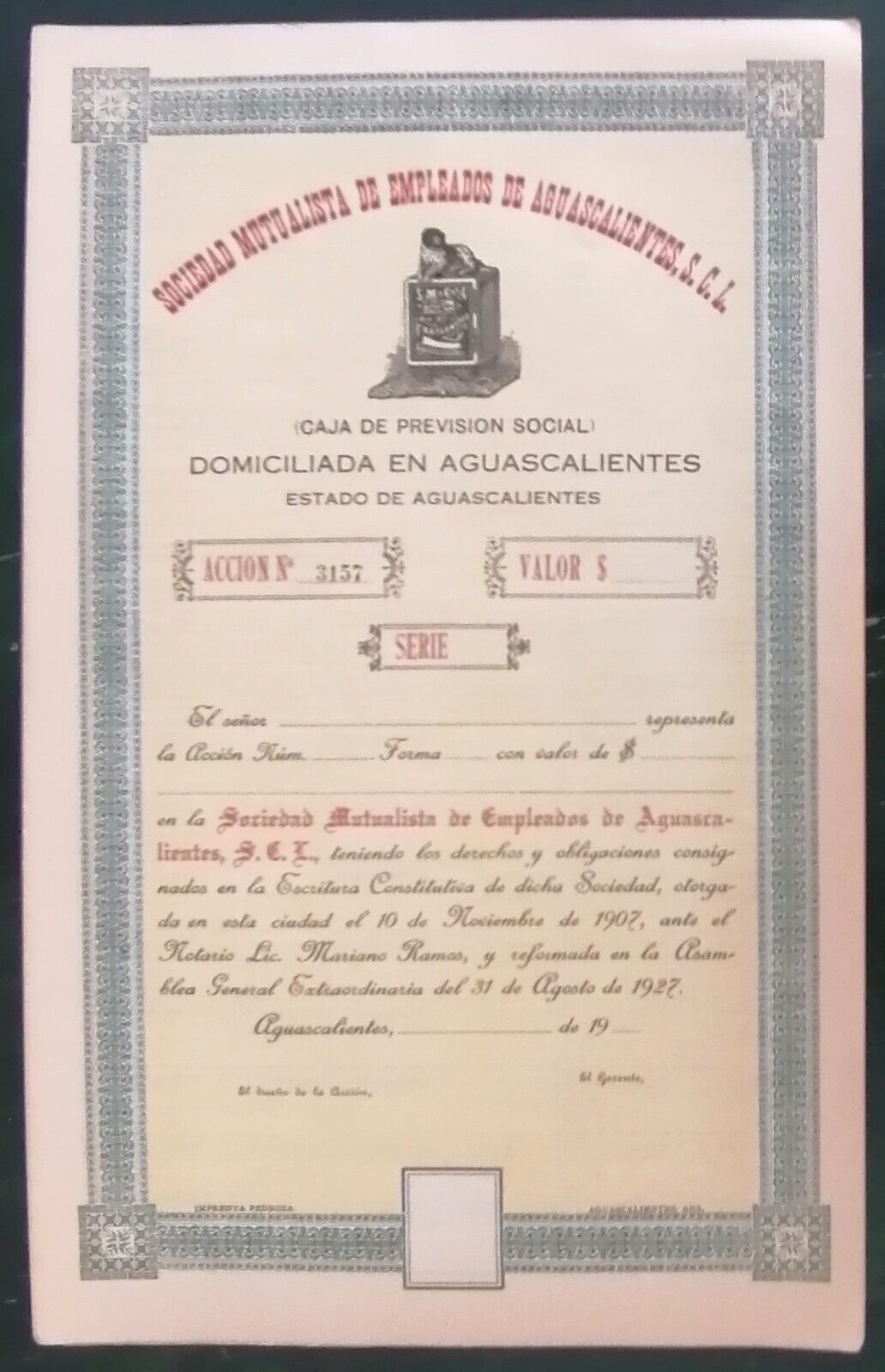

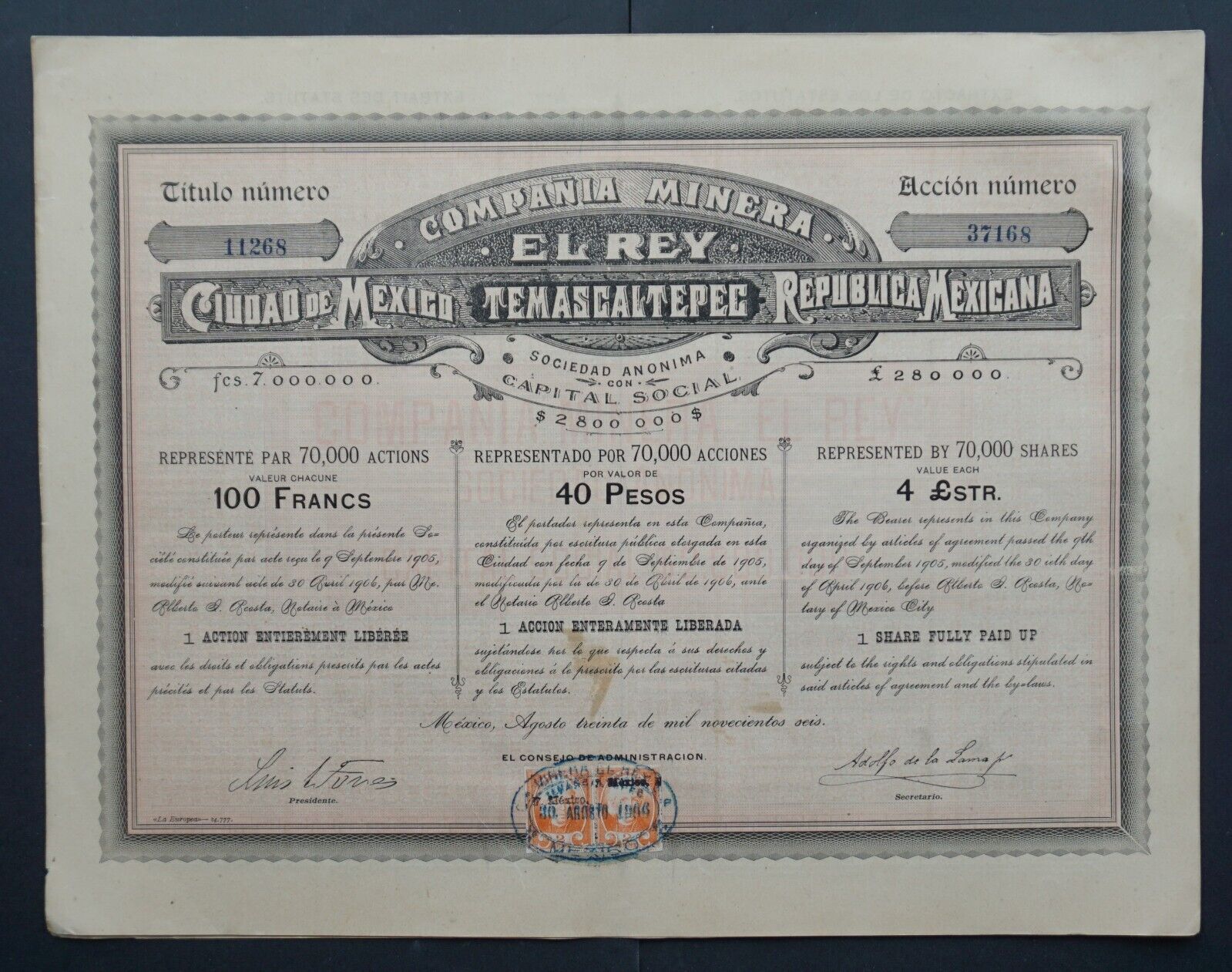

One share certificate of " THE OGILVIE FLOUR MILLS COMPANY LIMITED" Montreal(Canada) 1964 .Condition (opinion):Fine/very Fine(F/VF).brown.Printer:British American Banknote Company Limited. Illustration:Fort Williams Mills.

Some related information from the web:

Ogilvie's Book for a Cook: Historical Notes by Elizabeth Driver (Classic Canadian Cookbook Series)

Business and History - The Ogilvie Flour Mills Company, Limited

This material is from an alphabetical company list found in Business and History at Western at the University of Western Ontario.

This essay was written in

c 1967.

It was copied from the May 1967 "Centennial Issue" of

Industrial Canada

held in the Western Libraries at the University of Western Ontario. The original article should be consulted since this copy may contain some errors. The text and/or the images are being made available to researchers for scholarly purposes. They should not be used for commercial gain without the permission of the author or publisher.

When Sir William Van Horne, who pushed the Canadian Pacific Railway to completion in the 80's of the last century, was asked by a British visitor to name the national flower of Canada, he replied, "Ogilvie Flour, of course." The witticism had point: Ogilvie has been a household word in Canada since long before Confederation.

The first of the clan to settle in this country was Archibald Ogilvie, a prosperous Scot who carried 2,000 English pounds and three sons with him when he emigrated to Canada in 1800. Archibald's son Alexander erected a grist mill at Jacques Cartier, Quebec in 1801, moving in 1811 to Montreal, where he joined his brother-in-law, John Watson, in a new milling venture. Watson died in 1819, and almost 20 years later, in 1837, Alexander Ogilvie formed a new partnership with another brother-in-law, James Goudie. The old mill was transferred to a new one beside the St. Gabriel Lock of the Lachine Canal, which promised to be the key to future commercial development, as in fact it proved. When Goudie retired in 1855, Alexander's sons, Alexander Walker and John, took over, and the company name was changed to A. W. Ogilvie & Company. A third son, William Watson Ogilvie, joined them in 1860, completing a triumvirate that was to administer the family enterprise for 40 years. Their father, the first Alexander, had died in 1858, aged 80.

In 1886 work began on a modern mill in Montreal with the immediate objective of entering the British market on a major scale, in competition with Minneapolis millers. This new mill added 2,100 barrels of flour a day, raising the total production of all Ogilvie mills at that time to 5,500 barrels daily. The new unit was equipped with all the latest devices, including gradual reduction rolls, the so-called "Hungarian process" which combined stone and roller grinding to produce flours of previously unattainable fineness.

By 1888, when William Watson Ogilvie was alone in active management, the company owned mills at Montreal, Winnipeg, Goderich and Seaforth, as well as 20 grain elevators in Ontario, Manitoba and Northwest Territory. In 1895 William Watson Ogilvie was the biggest individual flour miller in the world, a power in business and financial circles, and a widely-respected philanthropist. He was the first flour miller to be elected President of The Canadian Manufacturers' Association. He died in 1900 and his surviving brother, Alexander Walker Ogilvie (who had retired in 1874) two years later. In 1902, A. W. Ogilvie & Company and W. W. Ogilvie Mill ing Company were purchased by a Montreal syndicate and re-named The Ogilvie Flour MillCo., Limited.

During both World Wars, when flour was, in effect, a munition, the output of The

Ogilvie Flour Mills

was an important factor in the struggle. Between the first and second wars, the company weathered boom and bust (in December 1932, No. 1 Northern Wheat dropped to 42 cents a bushel, the lowest price for grain since Middle Ages) and adopted the modern marketing methods, the new packagings and diversified specialty products that were among the innovations of the late 30's.

Cereal and feed mills were built in Montreal in 1940. Construction of the new Royal Mill in Montreal was begun in 1941 and completed four years later. In 1946 Industrial Grain Products, Limited, Fort William, was formed for the manu facture of wheat starch and gluten.

In the mid-1950's new developments took place as part of a major expansion. The Lake of the Woods Milling Company (established in 1887) was acquired in 1954, bringing the widely accepted brand Five Roses Flour under the Ogilvie roof. The

Ogilvie Flour Mills

Company, Limited, now marketed a complete line of baking flours cake mixes and hot cereals.

Another important step was the acquisition of Catelli Food Products Limited in 1959 with its variety of products under the Catelli, Habitant and Dyson labels. The sales of these products were extended into the United States market in 1966 when Catelli-Habitant Inc. of Manchester, New Hampshire, became a subsidiary.

Ogilvie Flour Mills

Ltd.

Administrative History

I

n 1163 Gilbride of Airlie, of the noble stock of Angus, knelt before William the Lion, King of Scotland and arose O'gille Buidhe, in Gaellic parlance "of the family of the yellow-haired." Thus began the lineage of the hydra-headed clan of Ogilvies, Ogilvies, Ogilvies & Ogilbies. Regardless of how the name was spelled, they were a formidable clan whose deeds traverse the path of Scottish history.

In 1750 Katherine & James Ogilvie celebrated the birth of their only son Archibald. The family were tenant farmers in Stirlingshire, and, as the sole male heir young Archibald grew to manhood and prospered. Fifty years later as the father of eight with five sons to consider, Archibald realized that there was little prospect left in Scotland for his children. Britain was forced to maintain a large army during the Napoleonic Wars and a young man's choice was conscription or the payment of twenty pounds to provide a replacement. Ogilvie felt that his money could be better spent in the pursuit of an improved life for his family in Canada. He gathered his wife, three daughters and his three youngest sons and set sail for the Colonies. In his possession were two thousand pounds and two fine French millstones. After thirteen weeks his ship dropped anchor in the St. Lawrence River beneath the Plains of Abraham. Archibald first touched Canadian shores garbed in the family tradition, knee breeches and top boots, with his wig firmly queued beneath a beaver hat. Advertising to all, that he was a Scottish squire and a gentleman.

The Ogilvie's arrival in Canada was impeccably timed; supplies that England normally imported from the Continent had been cut off by the War. The timber used in building ships for the Royal Navy, once taken from the Baltic States, was now coming from Canadian forests. The St. Lawrence was teeming with timber cruisers placing produce in heavy demand.

Archibald decided on a tract of wilderness in Howick near the Chateauguay River, some twenty-five miles south of Montreal. The first season, he and his family tried to carve out an existence from the feral land. The rigours of farming in a harsh and unpredictable climate did not agree with Archibald. For a price it was easy to rent a farm from the old Seigneurial holdings near Montreal and the following spring Archibald handed over the Howick tract to his son William. Taking his wife, daughters and namesake, Archibald leased the Ermatinger farm less than two miles from the waterfront in the current district of Maissoneuve. The third son Alexander retraced his footsteps back to Quebec City, setting up the two millstones at Jacques Cartier on the St. Lawrence. Only the swollen population brought on by the timber boom enabled a Scotsman to compete with the seigneurial mills, often in the hands of the local church.

That same year, 1801, John Watson a maternal uncle of the Ogilvie's arrived in Montreal and set up his own mill. Watson chose Nun's Island Channel, where the river gains speed. An outbreak of cholera in Quebec City had a deleterious effect on trade. Ships would not enter the stricken port and Montreal was forced to import flour overland from New York at a cost of a barrel. In 1811 Alexander joined John Watson at Nun's Channel adding his millstones to those of his uncle. In 1817 Alexander married his cousin Helen Watson and two years later took over the running of the mill following John's death.

The marriage of Alexander & Helen produced eleven children and it is this branch of the family that spawned the milling dynasty. The foundation was not built purely around the male heirs as many of the Ogilvie daughters married into prominent Canadian families. One daughter, Helen Ogilvie married, Matthew Hutchison who worked for many years as a flour inspector in Montreal and subsequently ran the Ogilvie mill in Goderich, Ontario. Margaret Ogilvie married George Hastings and four of their sons played prominent rolls in the Lake of the Woods Milling Co. Ltd. Alexander's own sister Helen married James Goudie, the son of a Montreal merchant. Alexander grew tired of the milling business and wished to spend more time at his farm at Cote St. Michel, outside the walls of Montreal. He entrusted the running of the mill to his brother-in-law James, who in 1837 attempted the bold venture of closing the Nun's Channel operation and opening a mill at the St. Gabriel Lock of the Lachine Canal. The new mill, situated in Montreal on a bottleneck to the sea, began to tap into the growing commerce and industry of the area.

Montreal experienced unprecedented growth in the early 1840's, reaching a population of 57,500. Alexander Walker Ogilvie, the seventh child of Helen and Alexander, wrote in his boyhood diary that the land of Montreal Island was becoming too valuable to farm and that he would have to chose another livelihood. But as was often the case in Colonial times circumstances in Great Britain altered greatly the new Canadian boom.

The Irish potato blight of 1846 caused the removal of all duties on foodstuffs eliminating any colonial preference and destroying Canada's advantage in the British market. Concurrently the bottom fell out of the British railway boom, timber crews came out of the woods that spring to find their logs unsaleable. The United States made matters worse by passing the Bonding Acts, designed at diverting the growing traffic from Upper Canada into American ports.

Following the ebb, the flow of commerce of the Canadian economy rebounded by 1850. The lure of the Canadian west beckoned and with it came British investment companies willing to take a chance on any get rich-quick-scheme, often to the detriment of their investors. This influx of cash and the general optimism in the Canadian hinterland soon returned Montreal to prosperity. James Goudie and his nephew Alexander Walker Ogilvie witnessed huge grain shipments entering Montreal from the Lake Ontario settlements. As many as 500,000 bushels of wheat passed through Montreal on the way to Great Britain. Goudie and Ogilvie believed that there was a market for flour and formed a partnership in 1852. This injection of new blood into the company was vital for the previous year Ira Gould had leased sufficient water from the Lachine Canal to operate several runs of millstones and had built the City Flouring Mill on lands adjacent to the Goudie-Ogilvie property. Gould's challenge forced Goudie and Ogilvie to renovate their operation. The resulting Glenora Mill added a new wing to the Goudie grist mill, relegating the older structure to storage space. The new mill stood four storeys high and contained equipment for such things as polishing barley. A steam engine was installed to assist the waterwheel.

Young Alexander Walker took to the milling business with exceptional zeal. The grain being produced in the older settlements was beginning to deteriorate, so he purchased grain from as far west as Niagara to assure the quality of his flour. He was also blessed with good fortune. In 1854, the Crimean War cut off Continental grain supplies, sending British buyers to Canada for wheat surpluses and available flour. At the same time American mid-west was burgeoning from squatters' shacks into full-fledged cities, eager to trade with Canada. That option was made all the easier when the United States passed the Reciprocity Treaty.

In 1855 James Goudie was able to retire knowing that Alexander was more than capable of running the business. He relinquished his remaining interest in the company to Alexander's younger brother John, who had recently returned to Cote St. Michael to help his father Archibald run the family farm. The sign on the Glenora Mill now bore the name A.W. Ogilvie & Co. The brothers had scant opportunity to bask in their accomplishments. Eastern Canada's wheat was rapidly declining and a Commissioner of Crown Land's report in 1856 suggested that there remained little quality land to be settled east of the Great Lakes. Annexation by the United States posed a very real threat and Canadian survey parties were dispatched to the Far West in search of suitable land for an ever growing population. Minnesota and the Dakotas were already being settled and a mill at St. Anthony's Falls (Minneapolis) was grinding 120 barrels of flour daily. Glenora flour was selling well from the St. Lawrence to Newfoundland and into the Maritime Provinces. The Ogilvie brothers felt that expansion westward was the natural progression. John Ogilvie began to push westward exploring new settlements and laying down offers to purchase against the upcoming harvest.

The 1860's brought another decade of feast and famine to the Canadian economy. Fortunately for the Ogilvie's they brought brother William Watson on board in 1860 to help navigate the company through the eddies of a turbulent time. Initially the American Civil War brought a huge increase to Canadian business, causing Montreal factories to operate non stop to cover all the war orders. More millstones were added to Glenora to keep up with the demand as the price of flour rose steadily. The Ogilvies rented extensive storage space to house all their grain pouring in from Western Ontario. However at War's end the victorious Union government took steps to block all Canadian imports, forcing many companies into ruin. A.W. Ogilvie & Co. was not among the casualties. The brothers cautious well organized approach to the milling business not only allowed them to ride out the rough economy but galvanized their position as one of the country's leading millers.

The company's new found security enabled a more pronounced division of labour amongst the brothers. John undertook the supervision of the family's interests in Ontario with an eye toward Western expansion. William Watson oversaw the administration of the company in Montreal, freeing Alexander to pursue public duties and to concentrate on the growing financial problems that were plaguing the flour industry. Alexander was elected to the Quebec Legislature by acclamation in 1861. His two terms in office were characterized by the most cordial of relations with his French-Canadian colleagues, for he spoke perfect french albeit with a Scottish burr.

While administering a successful business, he still found time for a staggering list of responsibilities that included: alderman for the City of Montreal, Justice of the Peace, President of the Workingmen's and Widows' Benefit Society, President of the St. Andrew's Society, the St. Andrew's Home, Caledonian Society, Royal Montreal Curling Club, Life Director of the Montreal General Hospital, Director of the Exchange Bank of Canada, Sun Life Assurance Co. and the Montreal Building Society.

A trip to Europe brought Alexander in contact with the "Hungarian Process" of milling that combined stone and roller grinding. The method produced flour of such fineness that Ogilvie introduced the steel reduction rolls to his Glenora Mills in 1871. By 1874 his myriad of outside duties caused him resign his position leaving William Watson in charge. In 1881 he was appointed to the Upper Chamber of the Senate. In 1884 Senator Ogilvie was one of select that toured the Western reaches of the Canadian Pacific Railway. C.P.R. General Manager William Van Horne held the Ogilvie name in the highest regard. When once asked by a visiting Brit what the national flower of Canada was, he replied, "Ogilvie flour of course."

The 1870's were years of expansion for the Ogilvies. In 1872 at John's behest a mill with a 250 barrel capacity was built at Seaforth, Ontario. Two years later a mill with twice the capacity and an elevator were built at Goderich. The elevator served the dual purpose of storing local grain as well as the water-born shipments from Western Canada. Later that year John Ogilvie ventured to the Dakota Territory and purchased the first parcel of hard spring wheat to be shipped to Eastern Canada. The 800 bushels proved to be of magnificent quality. The success of this experiment led the Ogilvie's to push for the growing of hard wheat in the Canadian West. For ten years John Ogilvie was a lonely visionary to the potential bread-basket available on the Canadian Prairies. In 1881 a mill was begun in Winnipeg and the first elevator in Manitoba appeared at Gretna. This was a calculated move for the arrival of the first Manitoba hard wheat in Britain had been a sensation. The early tests on the Manitoba product confirmed a grain of unsurpassable quality. The first export of wheat from Western Canada occurred in 1885 when the Ogilvie's sent a small shipment from the Winnipeg Mill to Scotland. The company received a staggering offer from British military for a half million dollar shipment. An order that far outstripped the companies ready supply but was a harbinger of the untapped economic potential in the Canadian West. By 1887 the Ogilvie's held two million bushels of Manitoba wheat in their elevators prompting competitors to complain that the company was out to corner the market. The future was so bright that not even the death of John Ogilvie in 1888 could dampen the desire to push westward.

The Ogilvies had no intention of selling wheat while the possibility of milling flour existed. They planned to tackle the rival Minneapolis millers head on and entered the British market on a major scale. To that end the Royal Mill was erected in Montreal in 1886 with an adjoining 200,000 bushel elevator. This new mill gave the firm a total production capacity of 5,500 barrels per day. To solidify their strangle-hold on the industry even further, the company purchased City Flour Mills from the heirs of Ira Gould, in 1893. That same year, in view of widespread want and hunger in Winnipeg, Ogilvie presented five thousand pounds of Hungarian flour to the city relief committee. The Company further encouraged further gift-giving by other local firms.

William Watson Ogilvie like his brother Alexander, had many civic responsibilities. He was President of both the Montreal Board of Trade and the Montreal Coin Exchange. He was the first flour miller to be elected President of the Canadian Manufacturers' Association and sat as a director with the Bank of Montreal, the Montreal Transportation Company and the North British and Mercantile Insurance Company. He was a member of the Montreal Harbour Board as well as being a Director of the Sailors' Institute.

In 1895 Ogilvie acquired Stephen Nairn's oatmeal mill in Winnipeg. That same year William Watson hosted a group of Minneapolis millers at a banquet in Winnipeg. One of the guests, C.A. Pillsbury of the great American milling combine, toasted the host as "the largest individual flour miller in the world."

G.R. Stevens, O.B.E. offers this interesting insight into the milling business in his book,

Ogilvie in Canada Pioneer Millers 1801-1951

: "During these pioneer years, when the milling industry was wracked with growing pains, a bitter struggle ensued between the millers and the farmers over the relative freight rates of wheat and flour. Few were as fortunate as the Ogilvies, who had both the raw material and the manufactured article to sell. In due course wheat won, with profound effects upon the milling industry. It became profitable to carry wheat rather than flour to centres of consumption; yet because of improvements in milling practice it did not pay to build little mills all over the place. A few large mills, strategically situated, proved the answer in Canada."

As the century drew to a close new and well-equipped mills began to spring up in many British ports. This practice permanently effected the market for imported flour as four out of every five bags of flour consumed in Great Britain were ground locally. The fifth bag was invariably used as a blend. One of the companies lucky enough to cut into that final 20% share of the market was Ogilvie. G.R. Stevens used this quotation from the British Baker's Manual of 1898 to illustrate the high regard with which Ogilvie flour was held. "Popular Penny Cakes for Counter Tray and Window" "For these lines there is something about Vienna flour which absent from nearly all of the others. There is only one flour that comes near it. That is made by Ogilvie's Royal Mill in Canada."

These words would have made fitting epitaphs for the two remaining Ogilvie brothers. After nearly a century in the milling business, the family was about to undergo a radical transformation. On January 12, 1900 William Watson Ogilvie died suddenly. In a fitting tribute the Montreal Stock Exchange suspended operations for the day. Obituaries from across Canada stressed the prominent roll that "The Miller King" played in the development of the North-West Territories.

Two years later on March 31, 1902 Alexander Walker Ogilvie died.

The Montreal Gazette

had this to say, "the death of few men would leave a deeper feeling of regret, or recall more sincere esteem and respect."

On May 30, 1902 the executors of William Watson Ogilvie sold the flour mills and seventy country elevators to a Canadian owned syndicate. The new president was Charles Rudolph Hosmer, a Montreal financier, born in 1851. He took his first job as a telegraph operator in 1865, moving on to manage a Grand Trunk Railway office the following year. Hosmer became the manager of the Dominion Telegraph Co.'s Kingston office in 1870, joining the Buffalo office the following and becoming superintendent of the company in 1873 at Montreal. He held this position until the company merged with Great Northwestern Telegraph Co. In 1881 he effected the organization of the Canada Mutual Telegraph Co. He remained the president and general manager of this operation until he joined the Canadian Pacific Railway as head of the telegraph department in 1886. Hosmer retained general management of C.P.R. telegraphs until his retirement in 1899. He was a director of the Bank of Montreal, C.P.R., Postal Telegraph, Sun Life Assurance of Canada and several other companies. His term as president of the newly formed

Ogilvie Flour Mills

Co. Ltd. ran from 1902-1927.

The new company needed someone with a strong knowledge of the milling industry, Frederick William Thompson filled that roll as the inaugural vice-president and managing director. He was born in 1862 and joined Ogilvie at the age of twenty. By 1889 he had been appointed manager of the company's business in the Northwest. Thompson took a prominent roll in the federal election of 1911, speaking out against reciprocity with the United States and opposing wider Imperial relations. He died prematurely in 1912.

The original director with the longest seniority was Sir Montagu Allan, who sat on the board from 1902-1951. Allan was born in Montreal in 1860 and was the founder of the Allan Steamship Co. and Matilda Caroline Smith. He was President of the Merchant's Bank from 1901-1922. Allan was created a knight bachelor by King Edward VII in 1906 and decorated Companion of the Victorian Order in 1907.

The other two original directors were Sir George Alexander Drummond and Sir Edward Seaborn Clouston. Drummond was born in Edinburgh in 1829, emigrating to Canada in 1854. He was a manager of John Redpath and Son, sugar refiners of Montreal. In 1879 he founded the Canada Sugar Refining Co. In 1882 he was elected a director of the Bank of Montreal, advancing to the vice-presidency in 1887 and presidency in 1905. In 1904 he was knighted.

Clouston was the son of a Hudson's Bay Co. Chief Factor and was born at Moose Factory on Hudson's Bay in 1849. He joined the bank of Montreal as a clerk in 1865. By 1887 he had risen to assistant general manager and became a first vice-president in 1906. He was created a baronet in 1908.

Just prior to the sale of A.W. Ogilvie & Co. and the W.W. Ogilvie Milling Co., F.W. Thompson received the Duke and Duchess of York at the company's Winnipeg mill. The royal couple carried out the customary inspection and the Duchess was said to be impressed by the cleanliness of the facility. At the end of his Canadian tour the Duke succeeded to the title of Prince of Wales. On March 1, 1902 the W.W. Ogilvie Milling Co. received the Royal Warrant from the Comptroller of the Household as Flour Millers to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales. When the Prince ascended the throne as King George V the Appointment was terminated. However in December 1912 a new Warrant was received as "Purveyors of Flour to His Majesty" an honour that the company held until December 11, 1939. The renewal of the Warrant indicates that the earlier recognition had not been a matter of protocol. It indicates that following the visit to the Winnipeg mill, Ogilvie flour had been adopted by the royal household.

Scope and Content

T

he first Ogilvie family mill was erected at Jacques Cartier in 1801. While the collection does not contain records back to the Company's inception, there are land deeds dating back to 1847 and material running concurrently up to 1983. The files include: financial records, income tax returns, shareholders lists, balance sheets and ledgers. The legal records include deeds, land titles and agreements. The corporate files (including ledgers) consist of Board of Directors minutes, annual reports, letters patent and correspondence from several

Ogilvie Flour Mills

Co. Ltd. presidents. There are administrative records that offer a glimpse into the day-to-day running of a flour mill with renovation costs and personnel files. The fond contains bound volumes of

The Jolly Miller

, the Company's publication. There are over 400 blueprints outlining the building of several facilities and close to 1500 photographs.

<div style="text-align:center"><a style="text-decoration:none" hrefid=AC1061546"><img src=

Your browser does not support JavaScript. To view this page, enable JavaScript if it is disabled or upgrade your browser.

Postage, including packing material, handling fees : Europe: USD 4.10 / USA $ 4.90 Rest of the World: USD 4.90

FREE of postage for any other additional banknote , stocks & bonds or other items

.

Only one shipping charge per shipment (the highest one) no matter how many items you buy (combined shipping).

Guaranteed genuine -

One

month

return

policy

(retail sales)

.

We invite

our

customers

to

combine

purchases to save

postage.

Full refund policy ,including shipping cost,guaranteed in case of lost or theft after the completion of the complaint with Spanish Correos for the registered letters (normally purchases above $ 30.00).

Old document for collection or historical purposes only.

Banknote Grading

UNC

AU

EF

VF

F

VG

G

Fair

Poor

Uncirculated

About Uncirculated

Extremely Fine

Very Fine

Fine

Very Good

Good

Fair

Poor

Edges

no counting marks

light counting folds OR...

light counting folds

corners are not fully rounded

much handling on edges

rounded edges

Folds

no folds

...OR one light fold through center

max. three light folds or one strong crease

several horizontal and vertical folds

many folds and creases

Paper

color

paper is clean with bright colors

paper may have minimal dirt or some color smudging, but still crisp

paper is not excessively dirty, but may have some softness

paper may be dirty, discolored or stained

very dirty, discolored and with some writing

very dirty, discolorated, with writing and some obscured portions

very dirty, discolored, with writing and obscured portions

Tears

no tears

no tears into the border

minor tears in the border, but out of design

tears into the design

Holes

no holes

no center hole, but staple hole usual

center hole and staple hole

Integrity

no pieces missing

no large pieces missing

piece missing

piece missing or tape